Author’s Note: For any student looking toward pursuing a higher education through college, phrases along the lines of “studying abroad will change your life,” are all too familiar. As someone who wants to study abroad, I try to treat these statements as true, especially after hearing personal stories from students who believe their experiences in studying abroad have changed their perspective. But what about teachers? Do they experience a similar shift in perspective after they’ve taught abroad to different students than they usually teach? I’ve decided to gather the experiences of teachers who have taught abroad in order to answer this question. For the people of BHS, here are their stories.

“It was July 18th, 2001, the first day we landed in Beijing. We got to the hotel and were all pretty tired from traveling, but we figured out that there was this big dinner. We were all partnered up with someone from China. I was partnered up with her, and I wrote in my journal that night, ‘I think I want to marry this woman.’”

One year later, they got married.

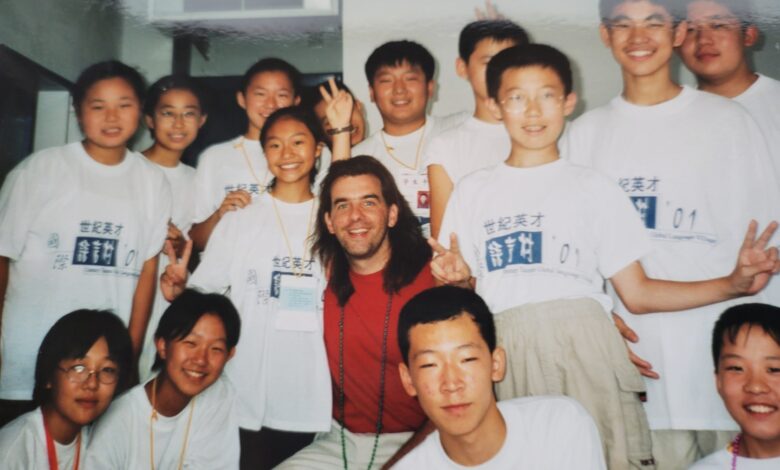

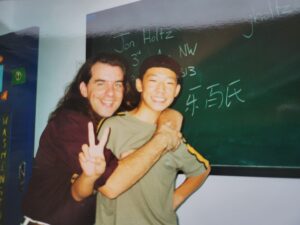

In the summer of 2001, Jon Holtz, an art teacher here at BHS, traveled to Zibo, China, to teach English at the Global Language Village. He was offered this opportunity through Concordia College.

“I saw an ad in one of our teacher newsletters: ‘Are you up for an adventure? Come teach English in China,’” Holtz said. “I was like, that sounds radical, and I’m probably not qualified. Let’s go anyway.”

Besides meeting the person he would marry, Holtz was exposed to the Chinese education system, which had glaring contrasts to the US education system. Holtz first noticed his students’ love of learning.

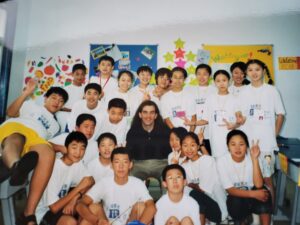

“This was a summer enrichment program. I had middle school kids, but you could tell they had a genuine thirst to learn,” Holtz said.

Along with their excitement about learning, Holtz’s students had an immense amount of self-discipline.

“The discipline of the kids is night and day [compared to BHS],” Holtz said. “You don’t screw around in China. There’s no margin for error.”

Holtz believes this combination of enthusiasm and discipline is informed by cultural pressures to strive towards perfectionism. This pressure creates an intense academic atmosphere, a common conception among Americans about Chinese schools. Chinese students’ intense academic rigor is particularly prevalent in their homework schedule, which would likely cause an uproar if implemented at BHS.

“I have a nephew in China. I was over there in the summer while he was in third grade, and mind you it’s summer and school’s not in session, but he still was doing three hours of homework a day,” Holtz said. “In China, they give you homework in the summer.”

The cultural pressure also causes young Chinese students to think about success and how to stand out at a very young age. Holtz was able to see this when he did an art project with both US and Chinese students.

“[When I came back to the US], I did a project in Art 1 where we had elementary kids write a short story and then illustrate it. When the kids did it, they were cute little stories: ‘I went and built a fort with my friend,’ or ‘We got a cat and a dog.’ The second year I did this I decided to try it with international students. My sister-in-law still teaches in China, and I said, ‘Hey, I want your kids to write these short stories.’ All of their short stories were about achievement, bragging and saying, ‘Look what I’ve done.’”

Besides the academic intensity, cultural pressures, and Chinese values towards education, Holtz discovered the students had an avid level of respect for both Holtz as a teacher and the building to which they attended school.

“When I would enter the room, all the kids would stand up, and I would have to give them the approval to sit,” Holtz said. “The kids clean the room at the end of the day. They don’t have janitors.”

While on a field trip with his Chinese students, Holtz was further exposed to the school’s strict environment imposed upon them by the principal, Madam Jong. He and his students were going to an amusement park, but, due to there being few “fun days” in Chinese schools, Holtz thought that this trip was too good to be true.

“In my head, I was like, ‘This isn’t going to happen,’” Holtz said. “I was right because word got out that a lot of parents were planning on meeting their kids there and bringing them snacks. Madam Jong put the kibosh on that and ended the field trip early.”

When I asked Holtz why she did that, he simply replied, “Control.”

“I don’t know if my experience abroad impacted me as a teacher,” Holtz said. “I don’t think they had healthy levels of pressure.”